towards the light

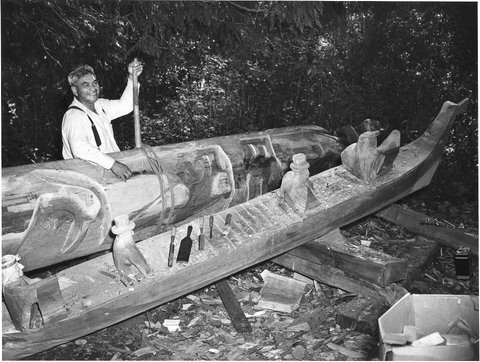

For our first Studio Focus of 2021, we caught up with Massachusetts glass artist Sidney Hutter, who can usually be found in his Boston area studio listening to Bob Dylan or Wilco, researching new methods, and creating new work. The studio is Hutter’s favorite place to be. He used these difficult Covid times to refine his studio practice and cold-working glass methods to create new works, finding a silver lining in the fact that the slowing of the business side of art allowed him to ramp up his creativity.

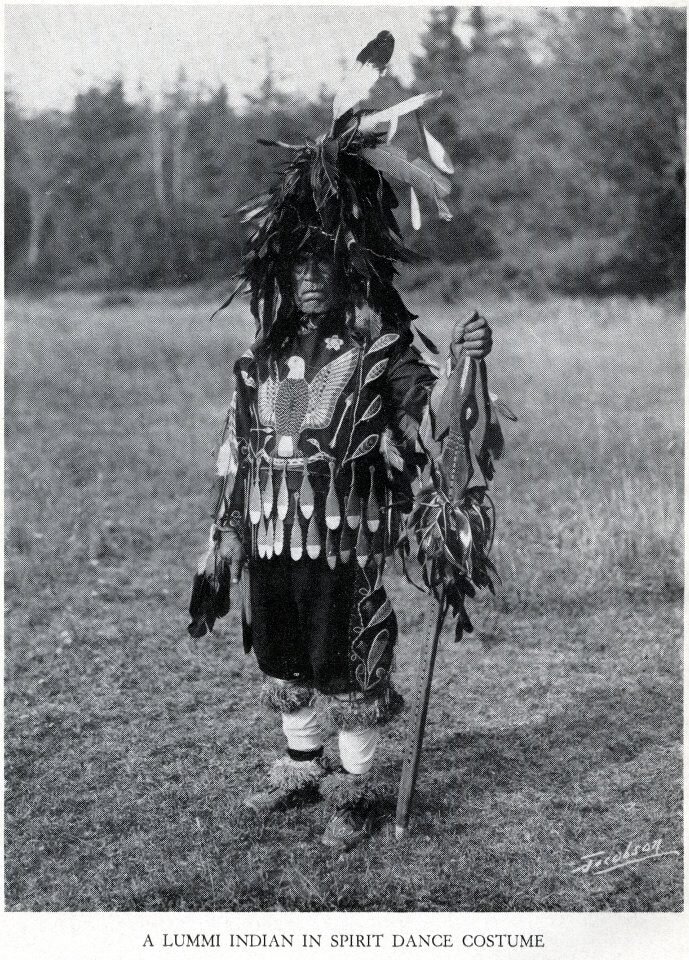

Sid Hutter in his studio during Schantz Galleries New England Studio Tour.

Hutter is well versed in hot glass techniques but most of his pieces are cold worked. After a fire rendered the hot shop at MassArt unusable in 1978, he began an adaptation to these circumstances that led to his innovative new technological methods for creating glass art. “It is amazing to behold how far the contemporary glass movement has come over 55 years or so,” he says while reflecting on the evolution of his medium since he began this artistic journey in 1974. Over the years, Hutter has never stopped innovating and exploring new ideas, even now through these unpredictable times.

Hutter studies materials and technologies often meant for other industries such as automotive or printing. He then repurposes them for application to his artistic practice. Since many of his vendors and services are deemed essential businesses—like the machine shop that makes medical devices—they have continued to be available during Covid without any significant stumbling blocks.

When Hutter began his long love affair with the cold-working process, there were not a lot of other glass artists using this approach. During college he worked alongside, and learned from, fellow Schantz Galleries artist David Huchthausen. Much of Hutter’s methods are self-invented. His studio space is constantly evolving alongside his work and is as unique as the pieces of art that come out of it. “If I need a tool to make something, I will get it or make it. I am definitely a tool guy. I don’t do as much hand stuff as I used to, but I facilitate and do all the testing and research on equipment to get it where it needs to be.”

A child of two college professors, Hutter is naturally inclined to the pursuit of knowledge. “ If I get interested in something, I start to pursue and research it, then I start making phone calls to source the materials. It’s an itch I have to scratch until I figure it out, then onto the next itch.” Hutter is currently researching and testing new adhesives and materials from 3M. While not all of his research goes according to plan, his successes result in eye-catching pieces that merge new technological breakthroughs with classical ideas of art and beauty.

While Hutter’s innovative work looks modern, it often carries a storied past. He often repurposes salvaged glass in addition to using new plate glass. He tells one story of how he was able to recycle glass from the Hancock Tower in Boston:

““When I was at MassArt, a fellow student, Joe Upham, knew Jerry Ellis, the owner of Building 19, who had bought remnants from insurance companies to resell. He had acquired all of the damaged glass from the Hancock Tower, warehousing it in Lynn, MA. We used to take the school truck to get the broken sheets of glass that were unsalable. We then melted the clear glass in a furnace for blowing. Joe was making goblets, which he then took to the Hancock Tower to sell to the building employees. I was using the mirrored glass with a reflective coating for making my sculptures. The Hancock is probably my favorite building in the whole world both because it has so much personal meaning while also it is an amazing architectural obelisk of 1970s construction. Or failure of architectural technology, I suppose, since the reason I ended up with the glass is that they miscalculated the stresses on the windows from the wind factors.”

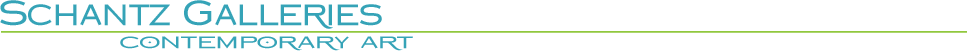

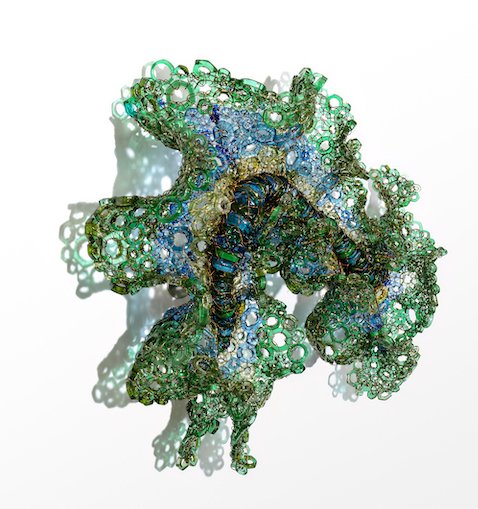

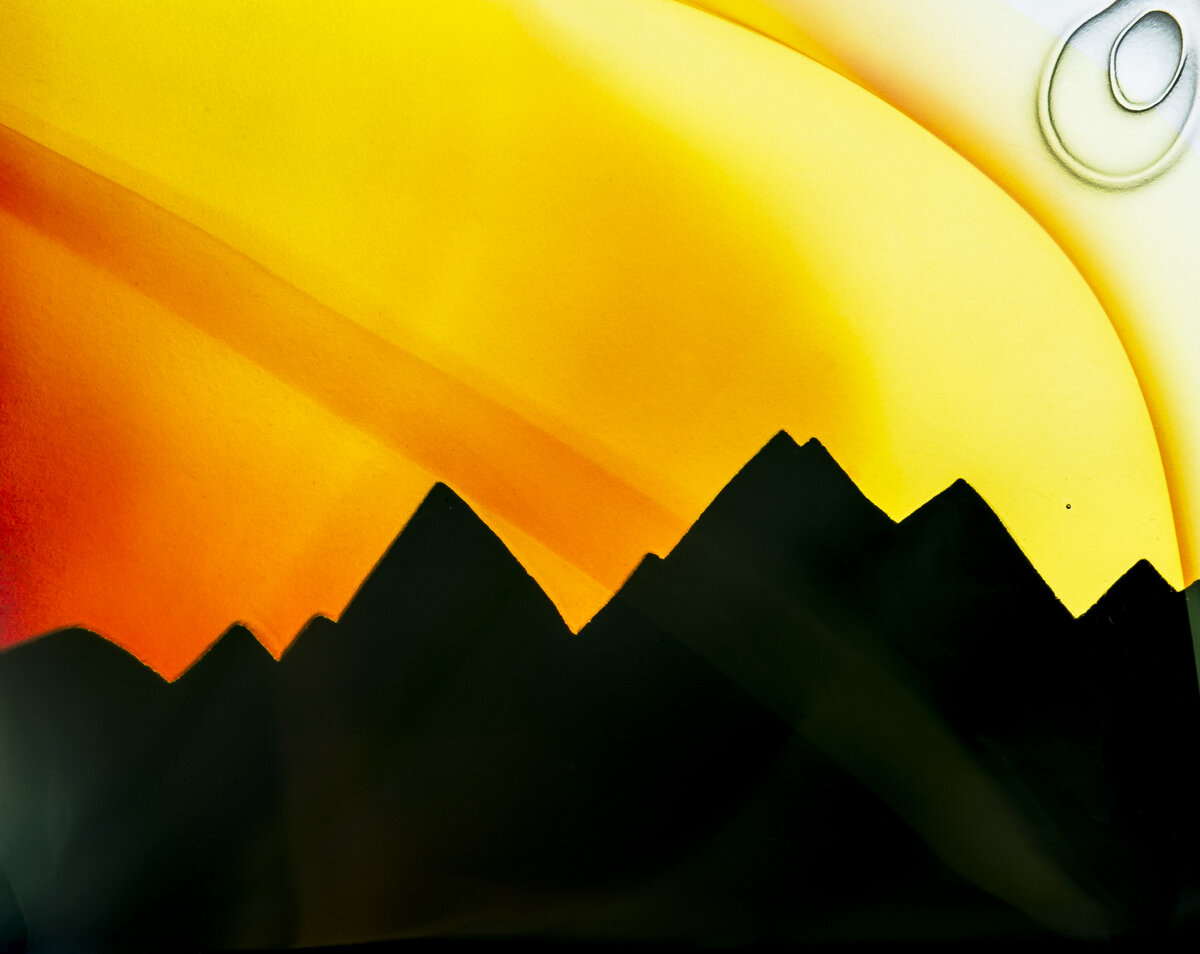

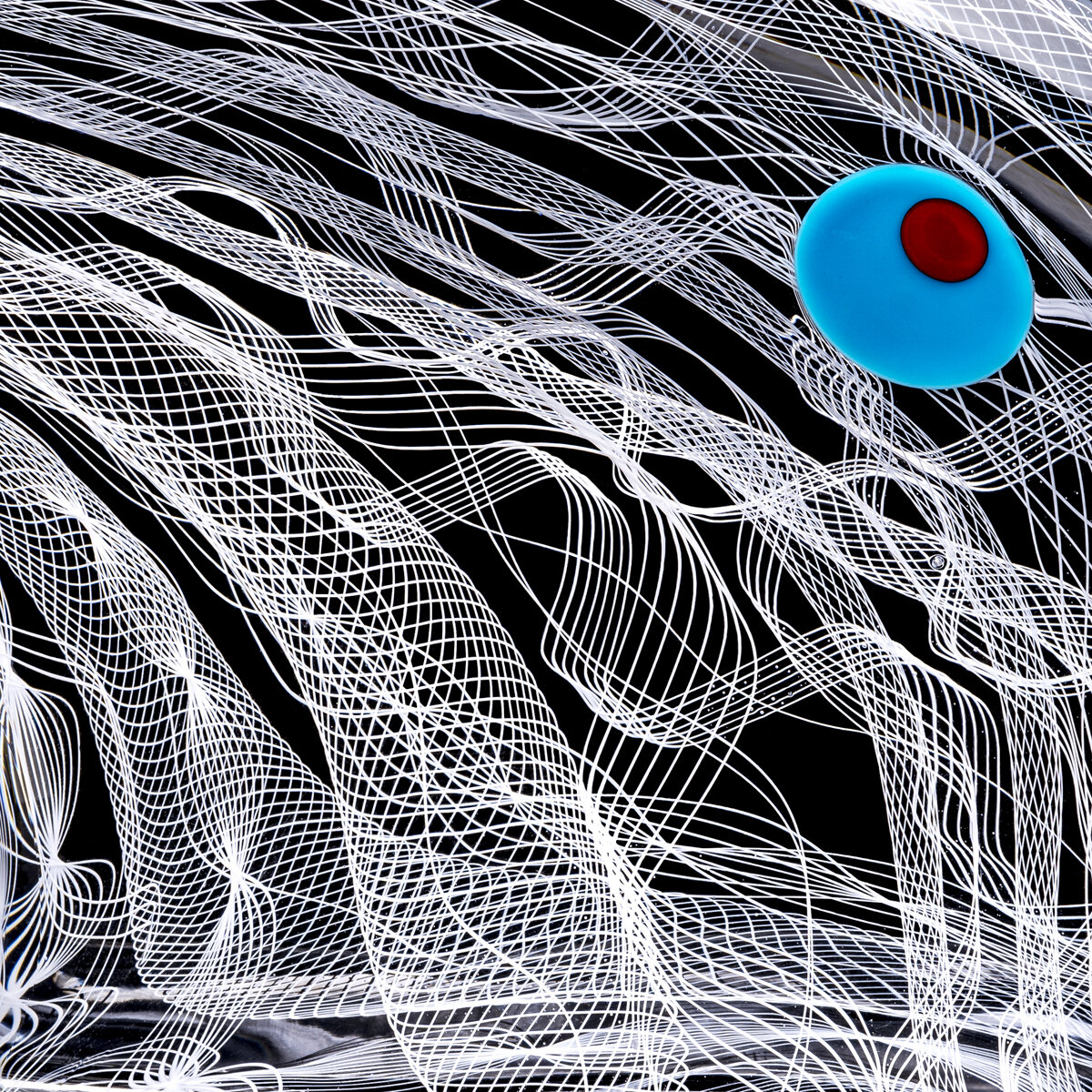

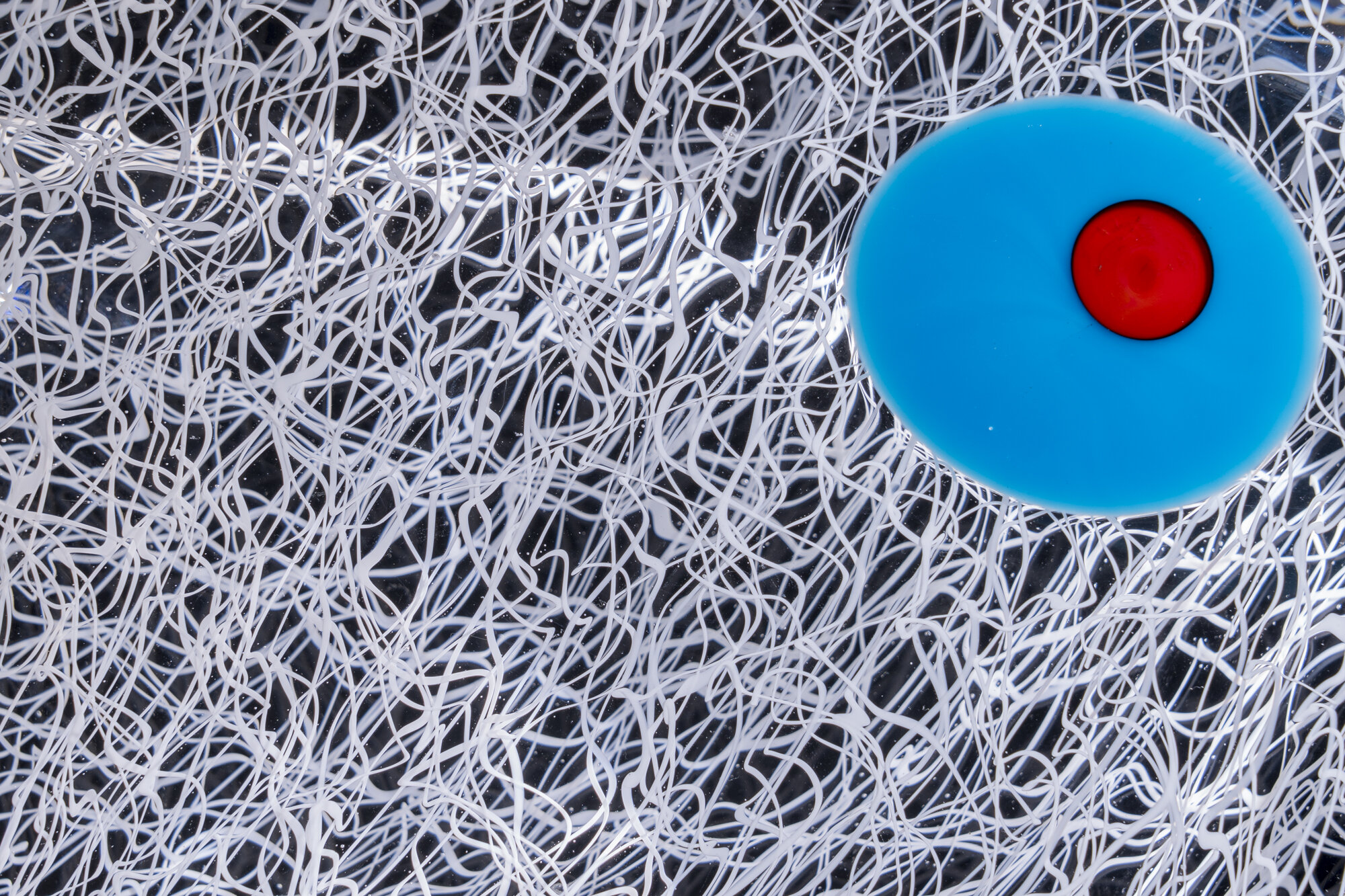

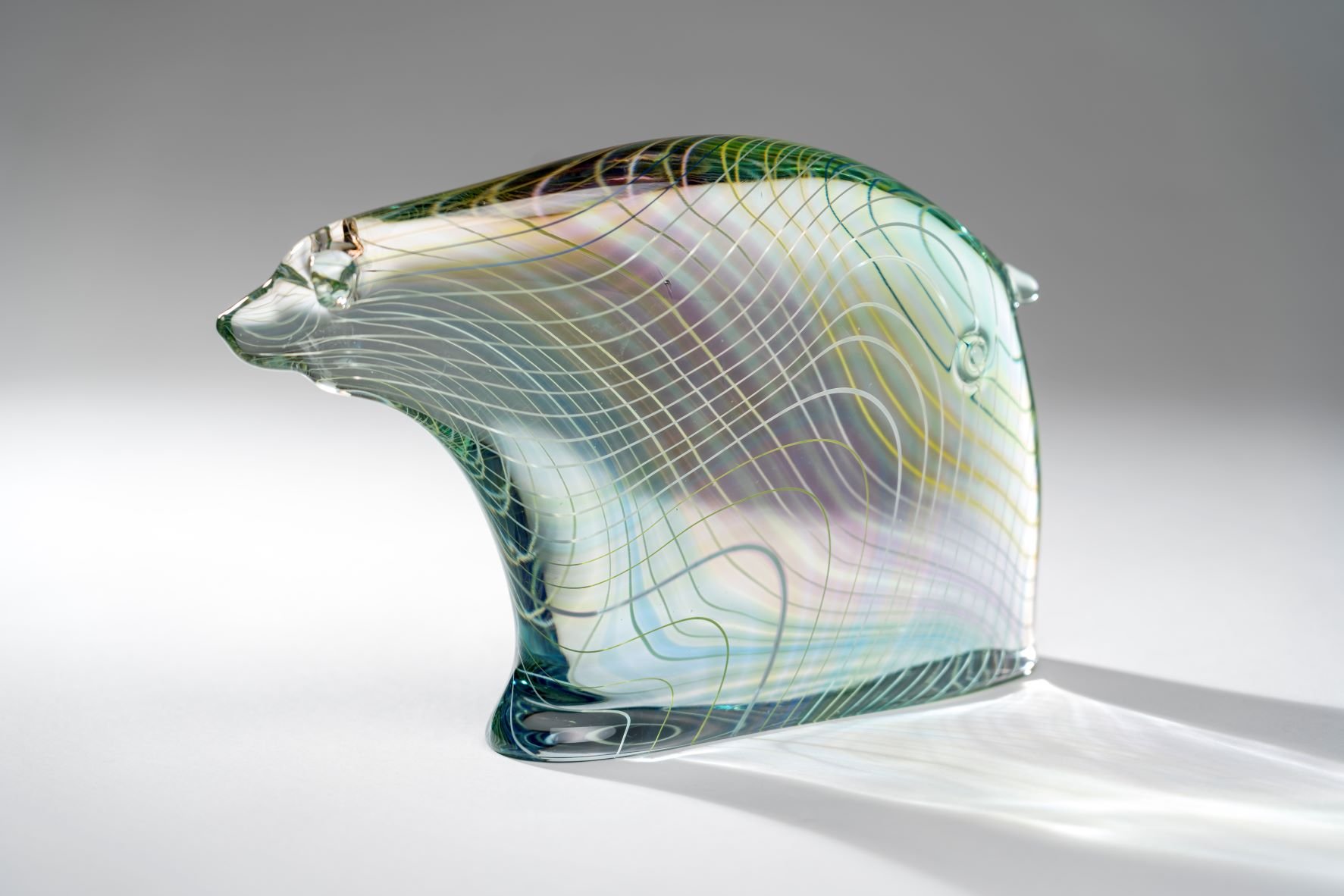

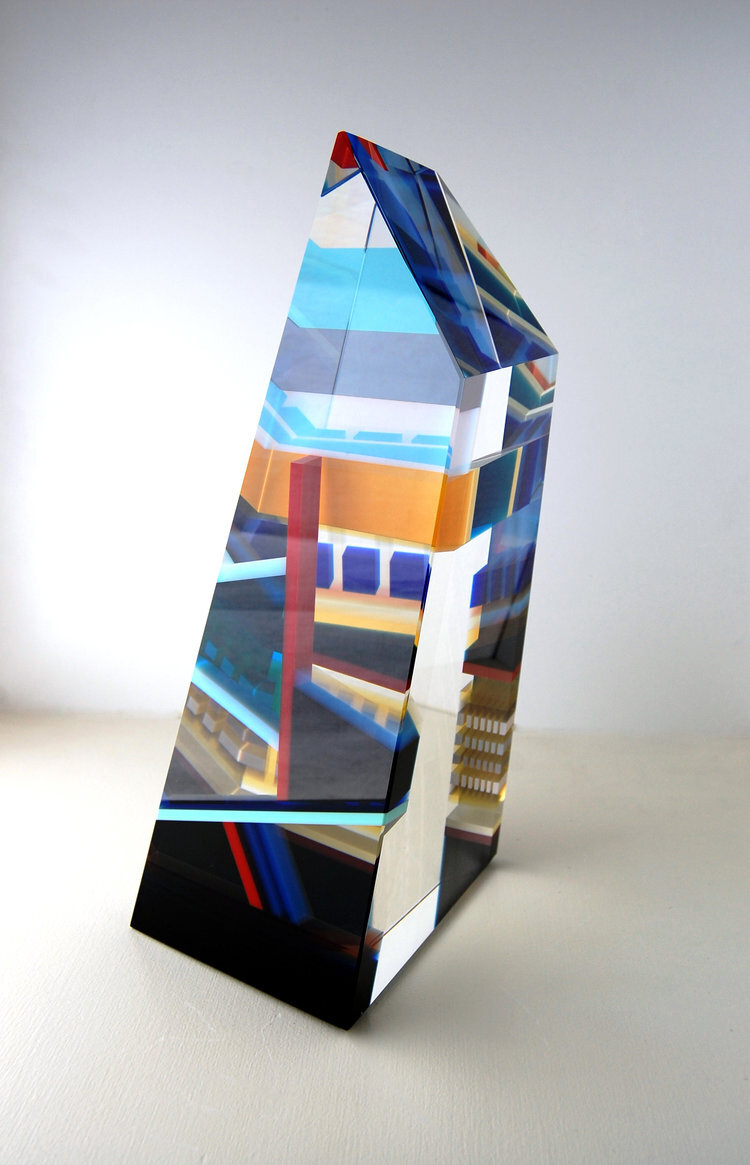

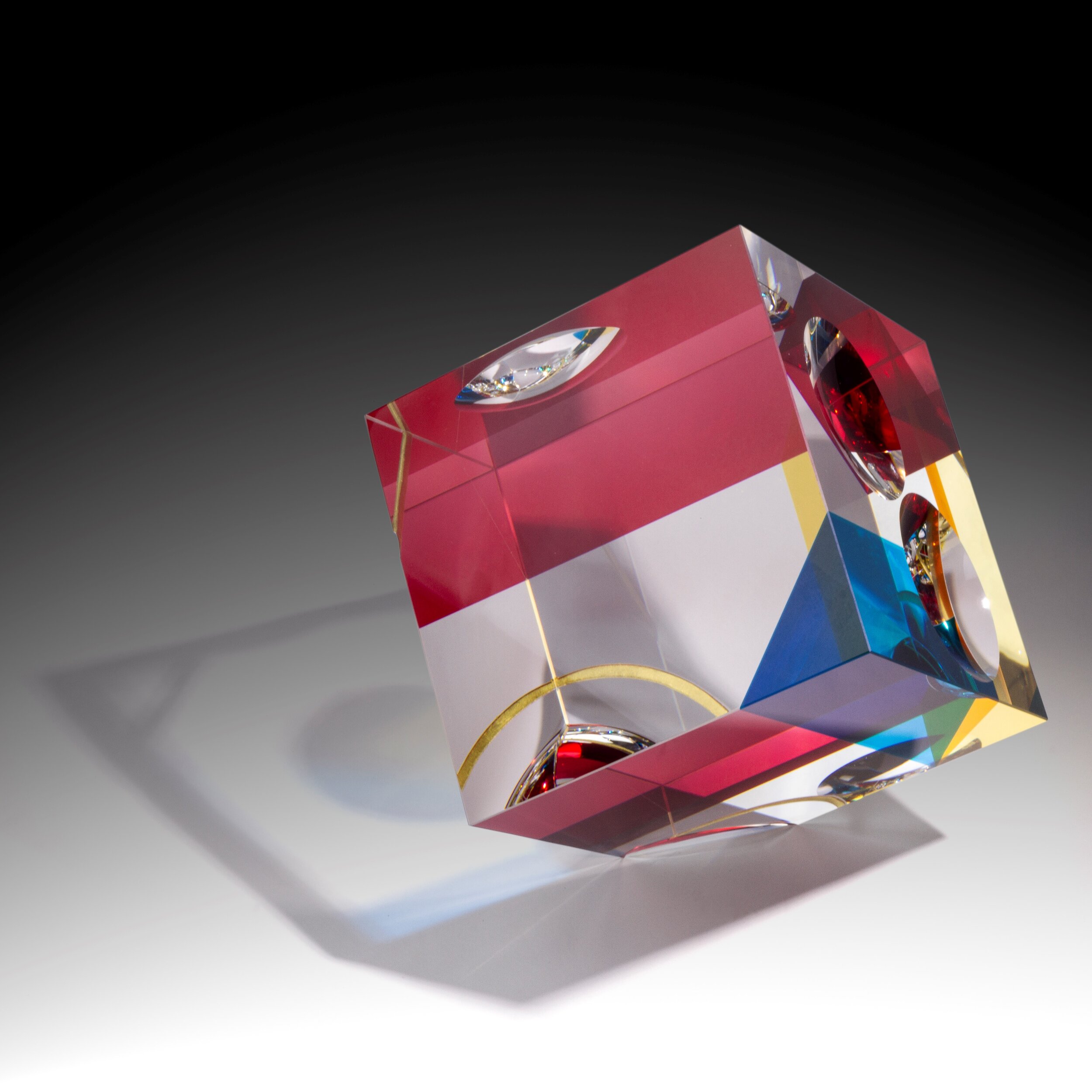

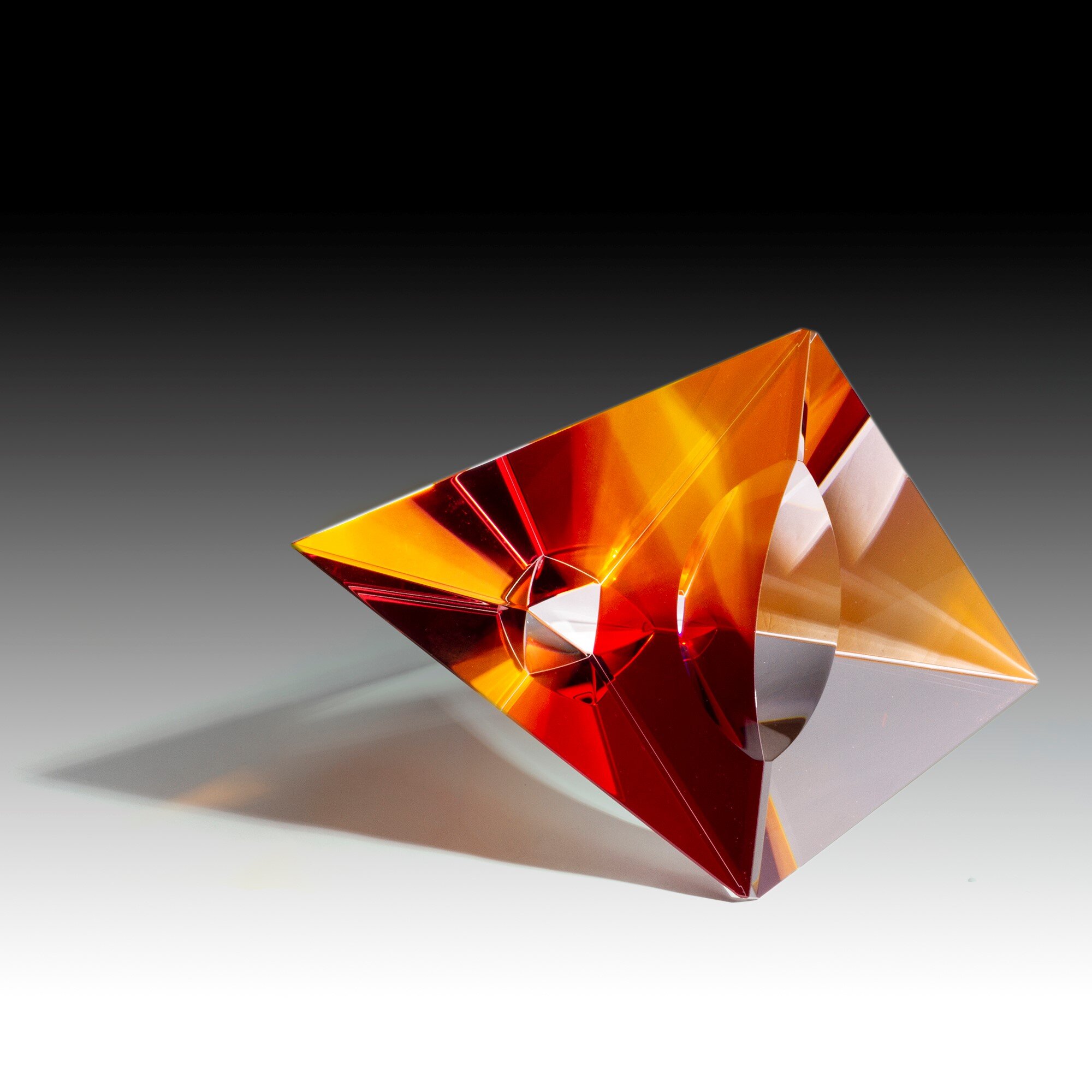

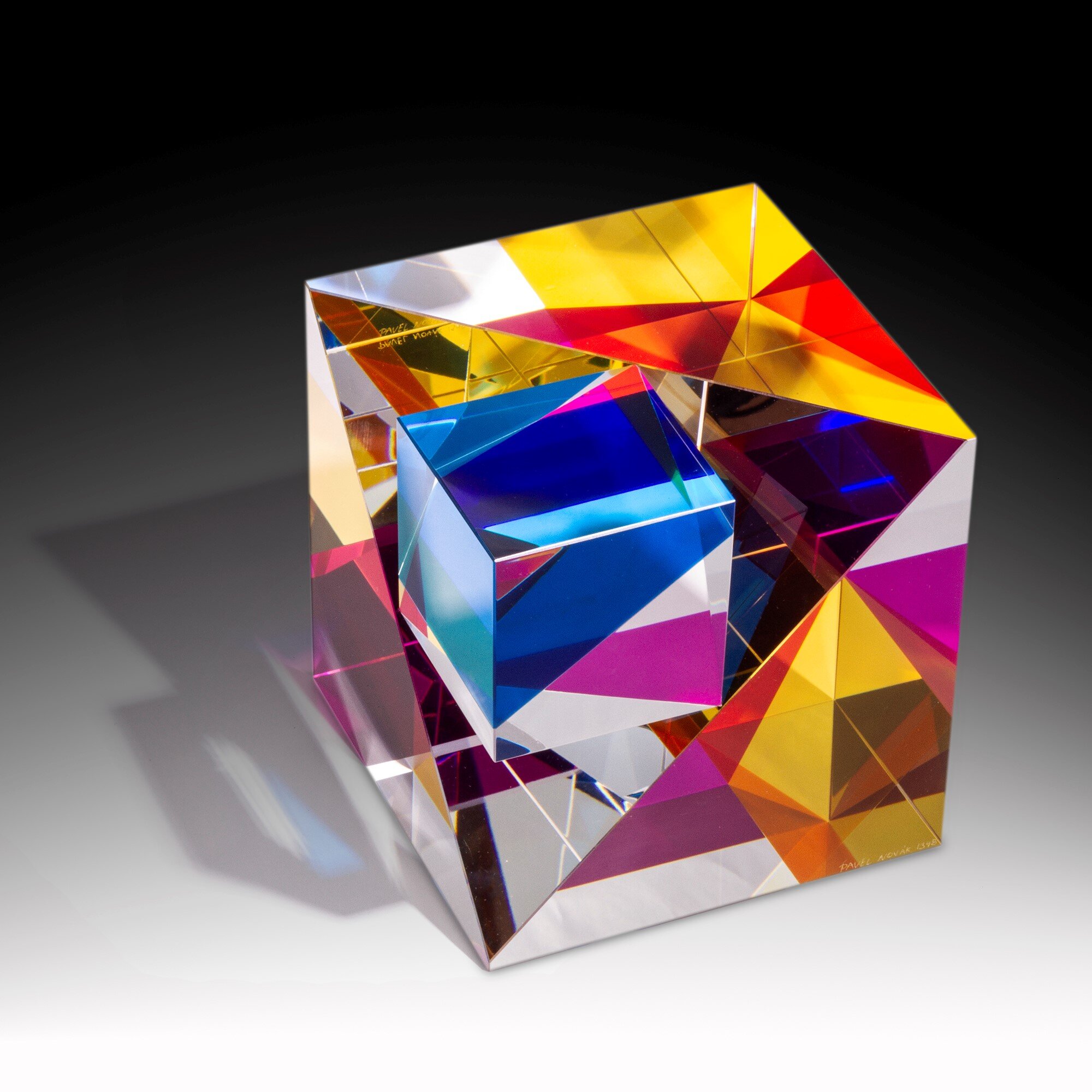

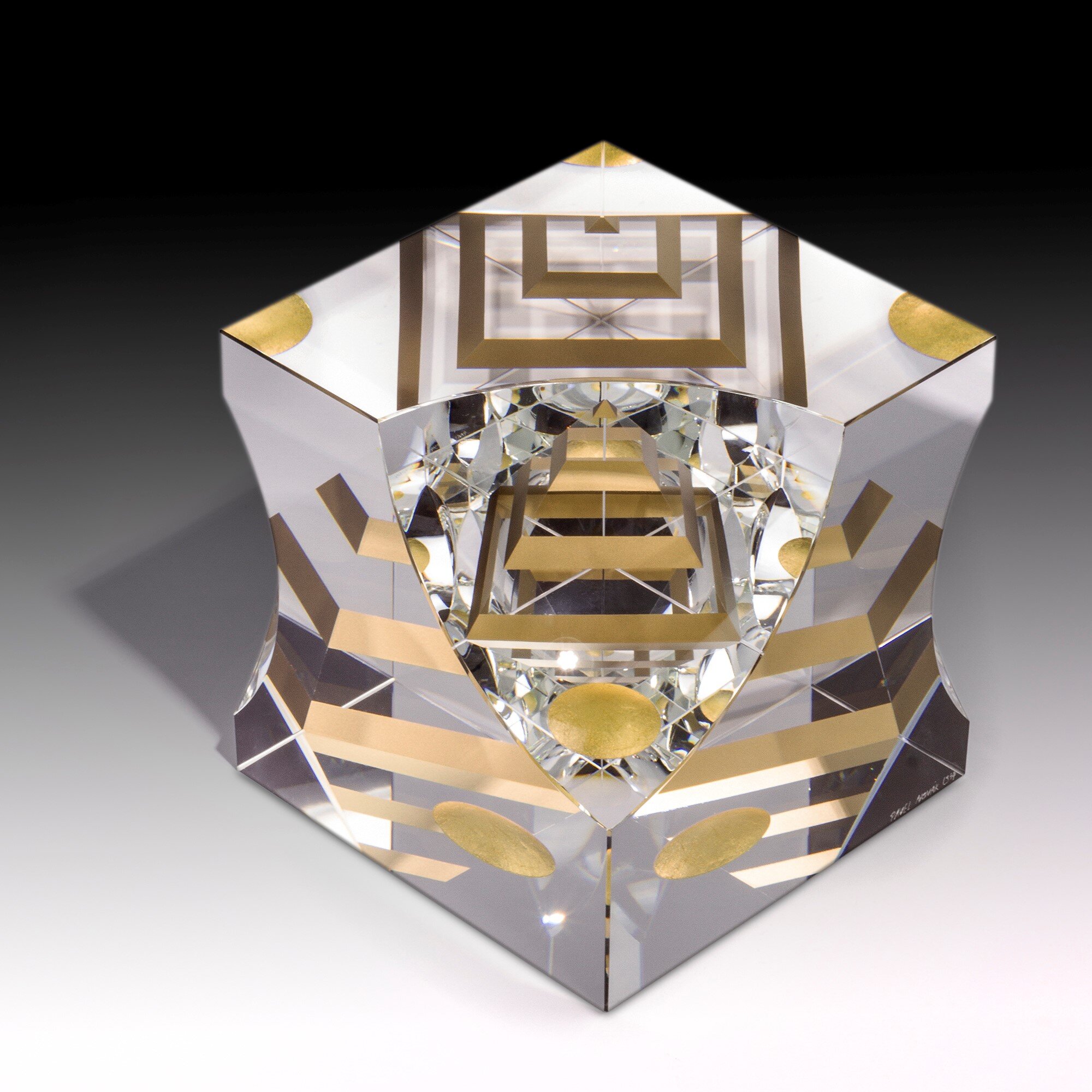

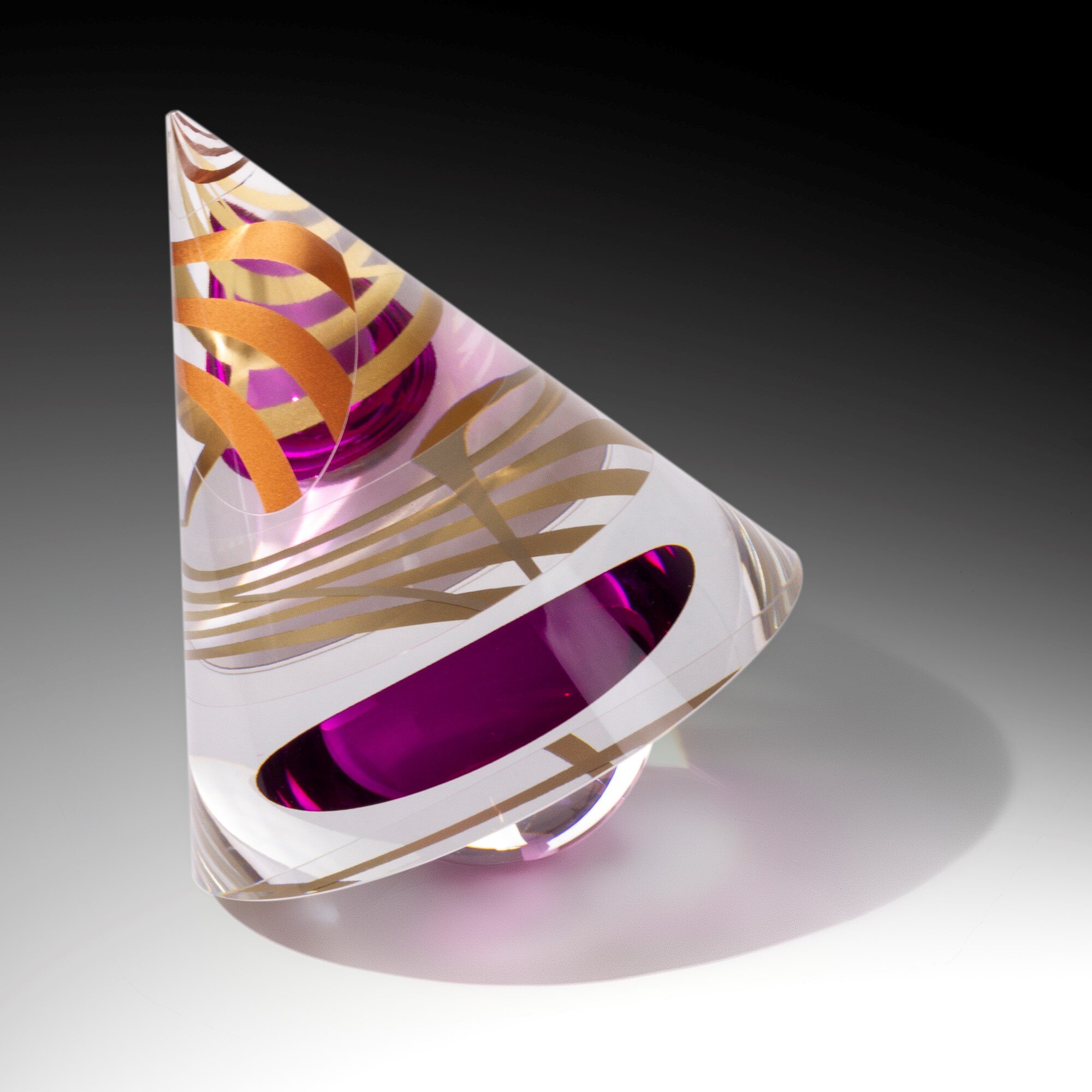

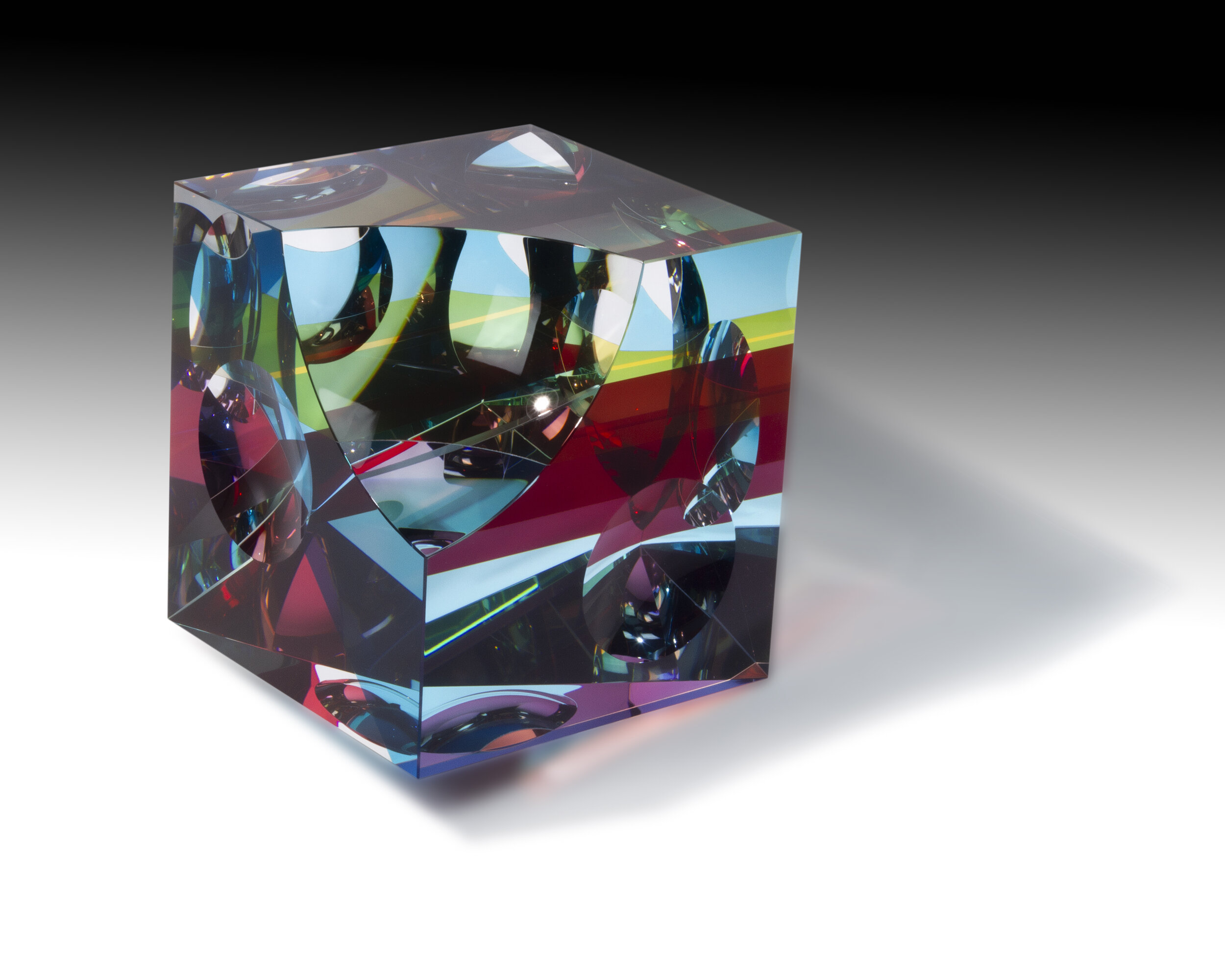

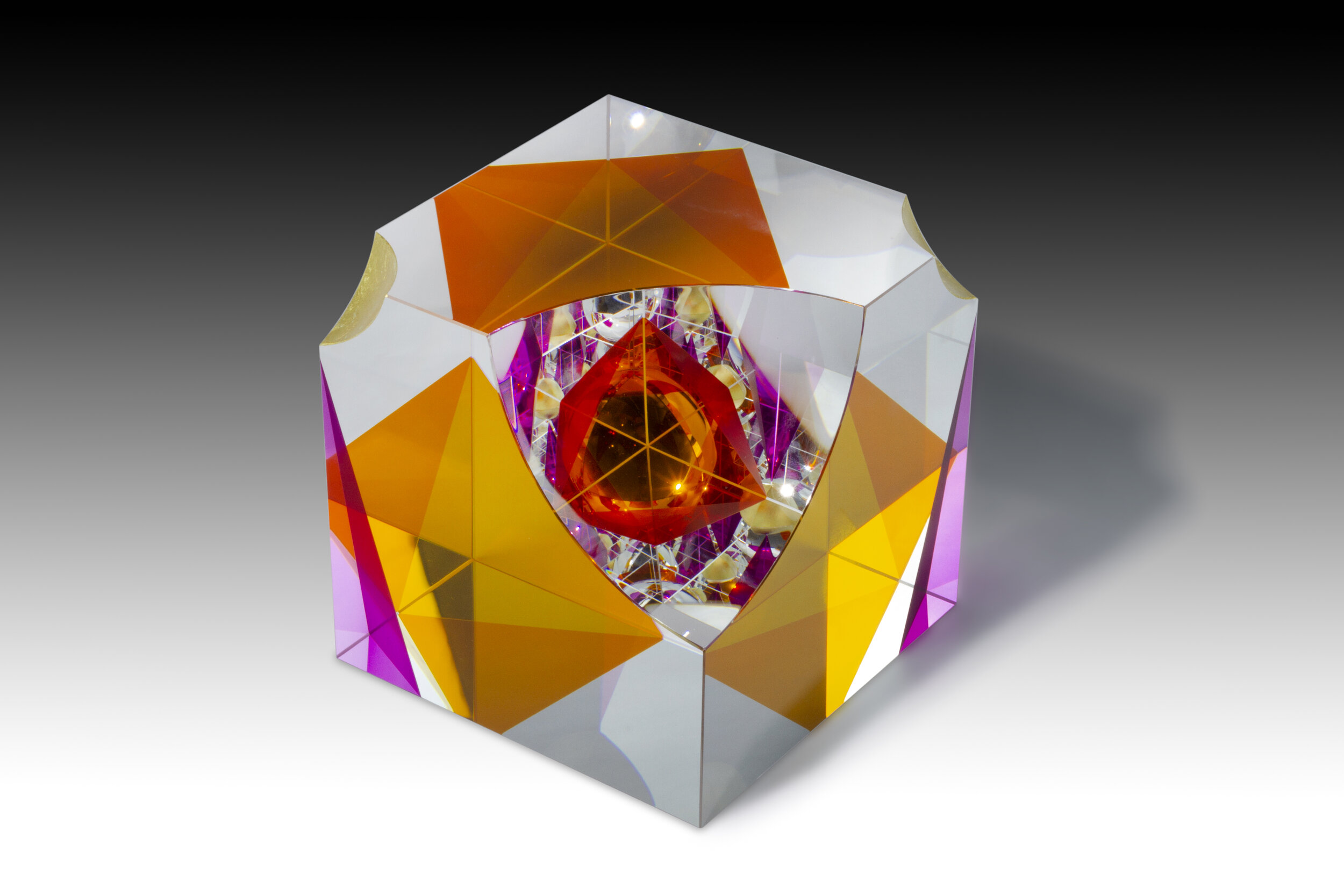

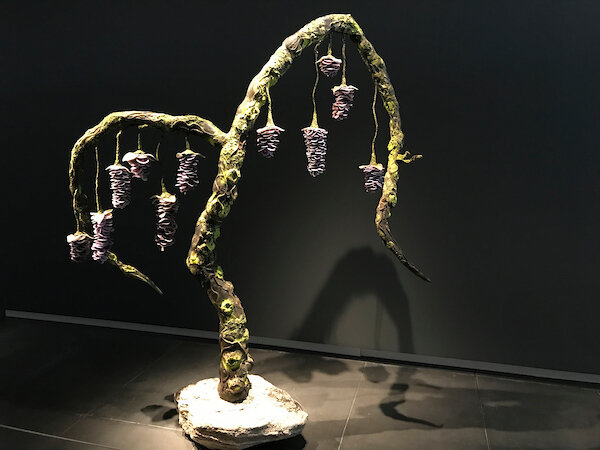

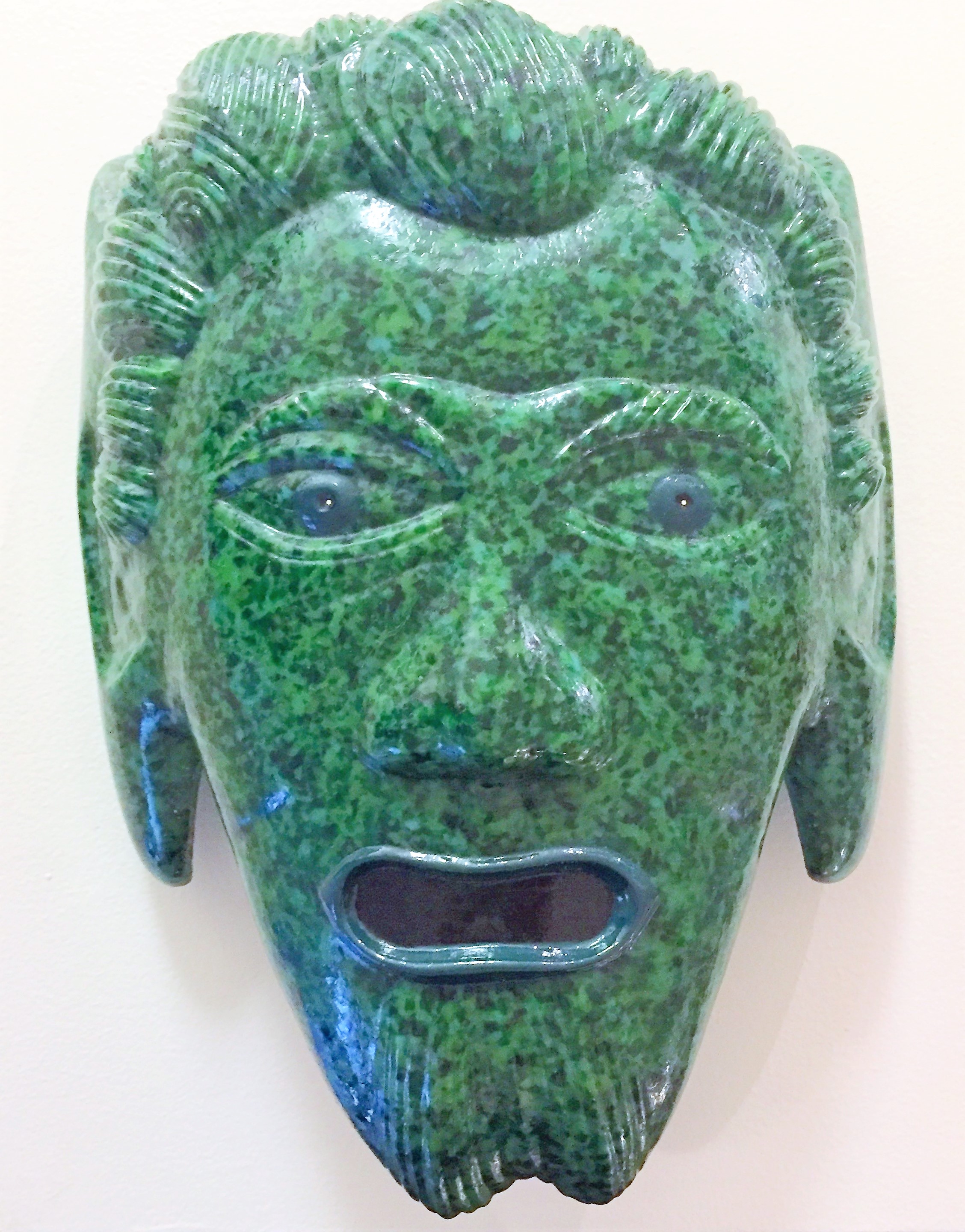

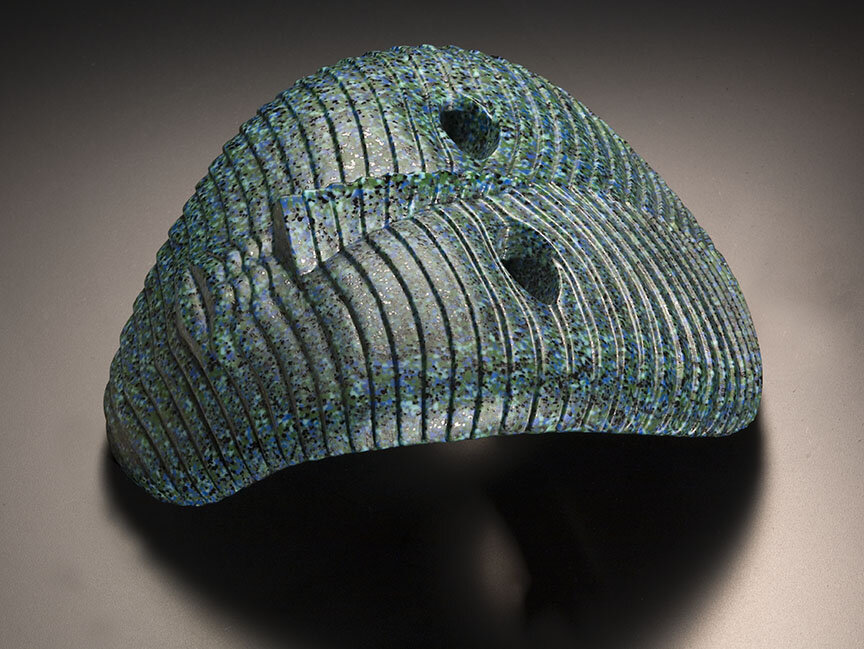

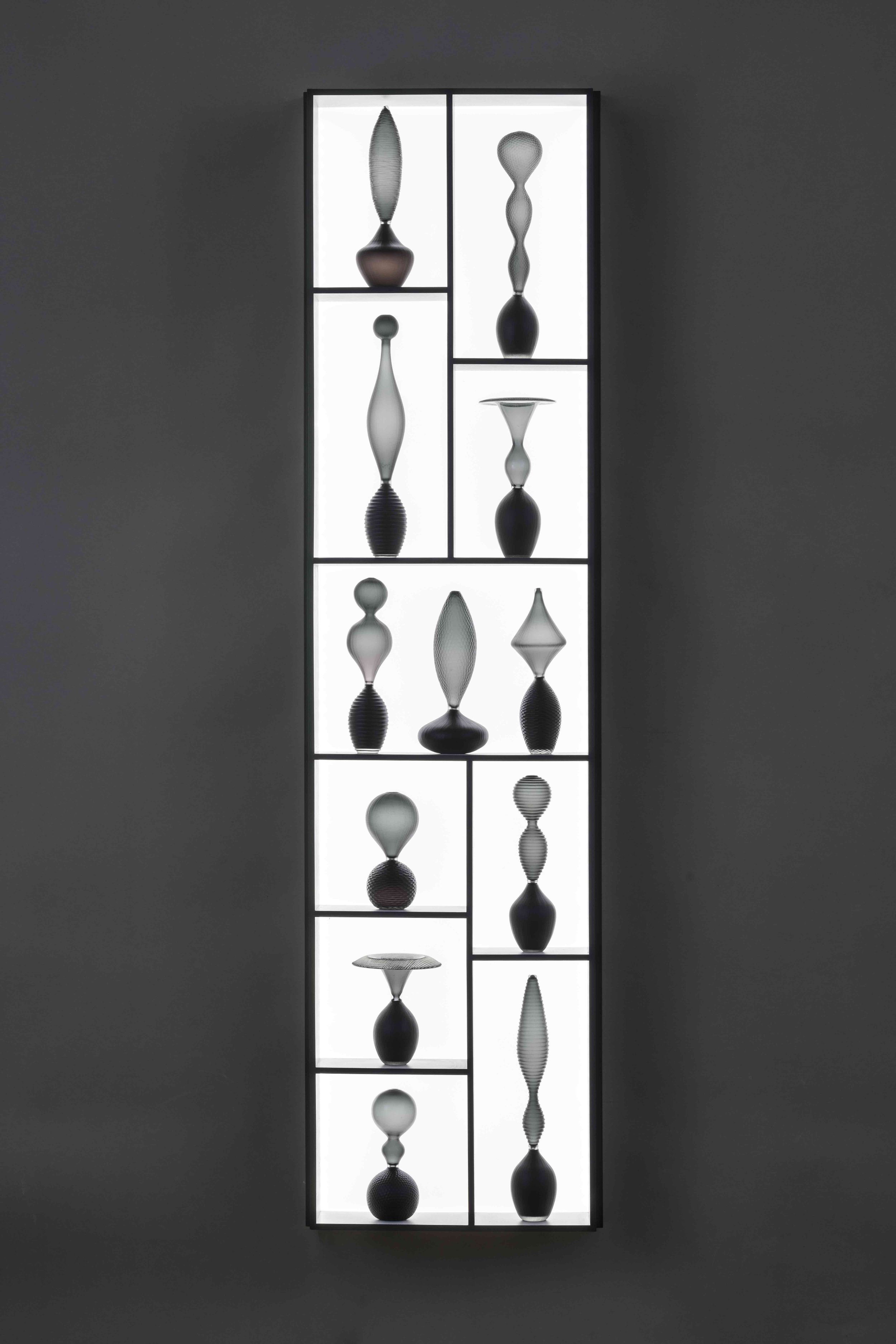

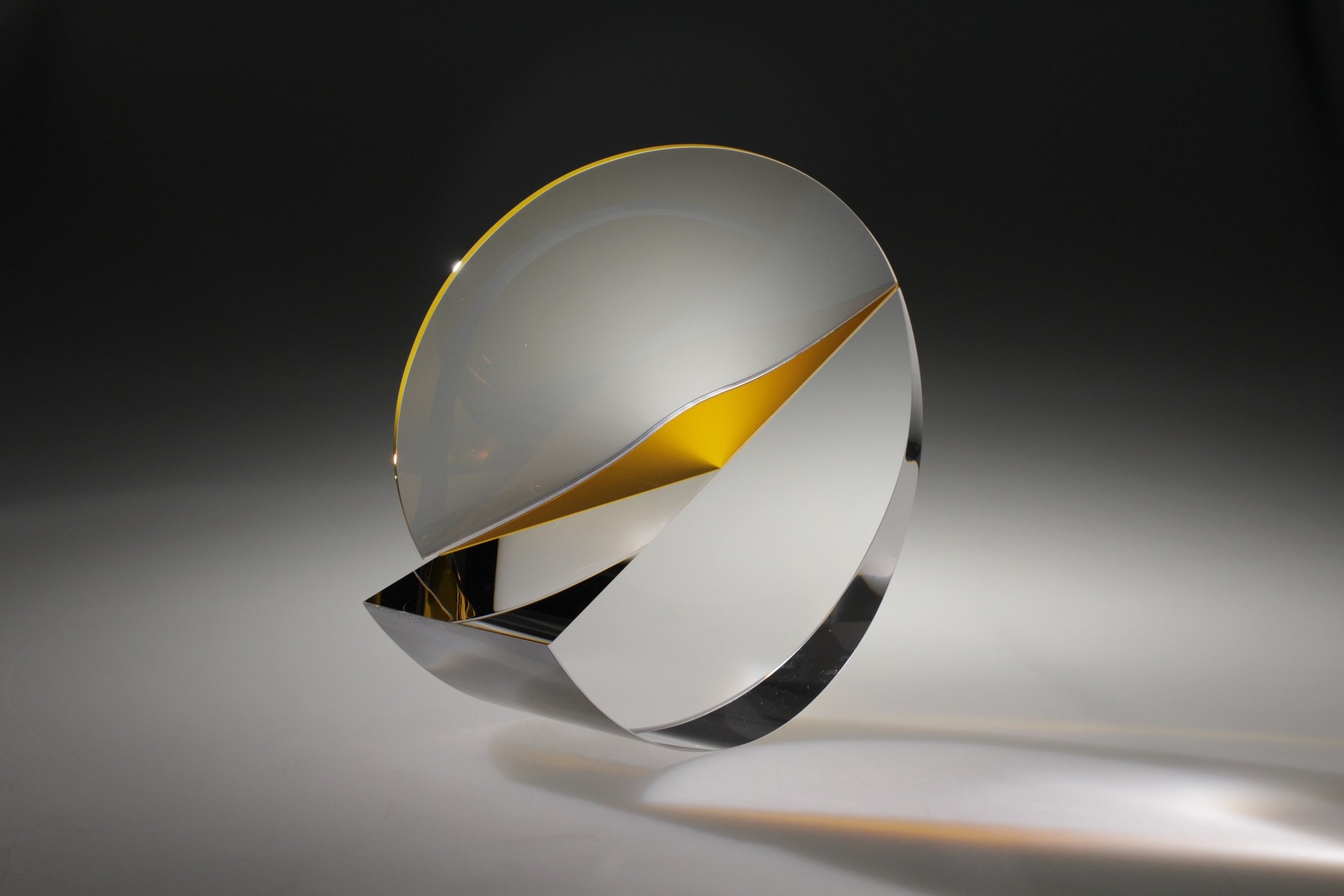

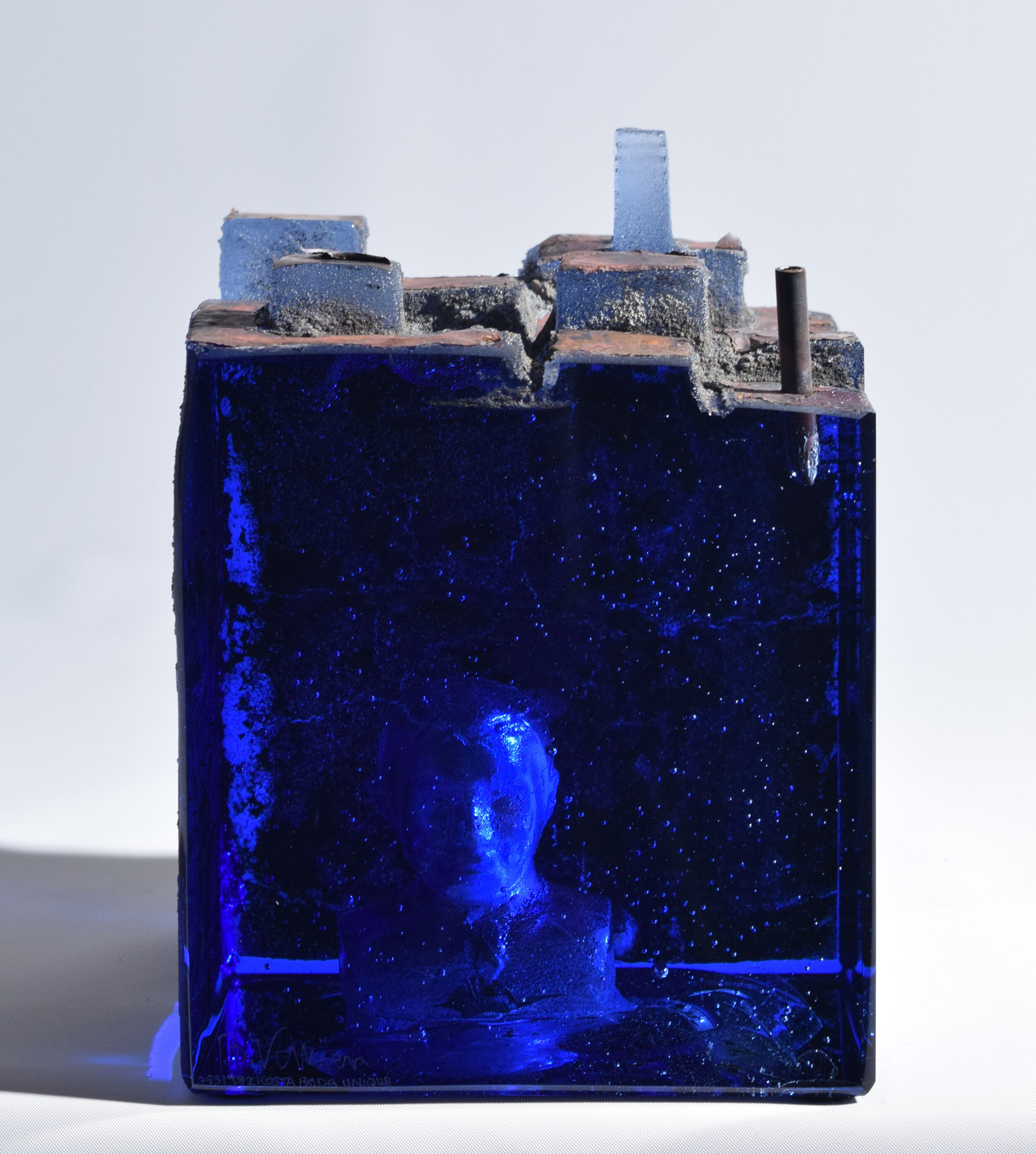

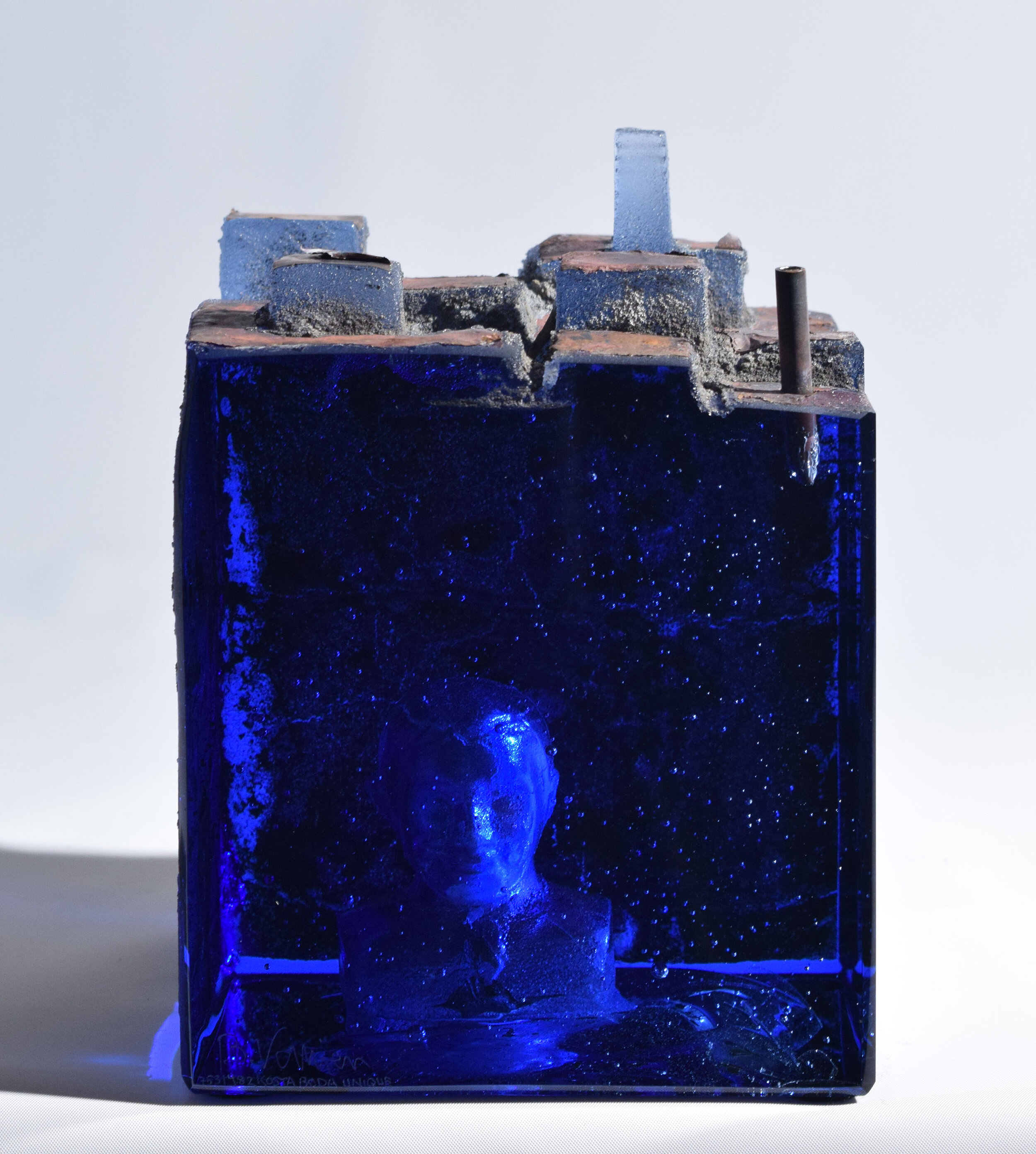

Examples of Hutter’s Light Works through the years…

View Ner Tamid to music by Pink Floyd!

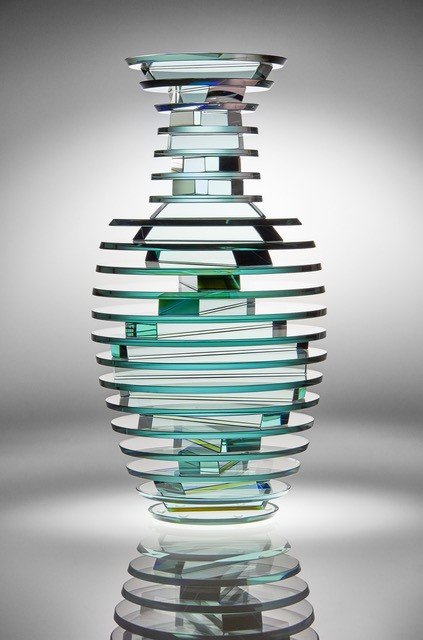

While all of Hutter’s objects, from his functional lighting work to his large sculptural pieces, are interesting and complex, his classic vase forms most often catch the eyes of visitors to Schantz Galleries. They are primarily constructed of cut, ground and polished plate glass which Hutter assembles using pigmented colored adhesives, which results in overlapping planes of color that appear to fill and empty his vessels depending on your viewpoint. Hutter pursues this juxtaposition with intention and thought. “The genesis of the plate glass vases was that I couldn’t blow glass but still wanted to make vases. When I started to work with that concept it became about how a vessel can be reinterpreted as something it isn’t. When people say “that’s a vase but you can’t stick a flower in it”—that’s right, but you are also looking at a volume that is describing an object- classical yet both utilitarian and decorative. My vessels are shaped like an amphora from Greek and Roman times yet they are reinterpreted in many different ways.” Hutter sees possibility in simple origins, saying “My philosophy of art is that there are 3 shapes and 3 colors; there are squares, circles, and triangles, and there is red, yellow, and blue. That is where it all comes from.” Within his obvious appreciation for the foundation of art, his own way of interpreting these simple ideas brings a complexity and interest all its own. This is how he creates such unique works. He says “the thing I pride myself on most is when people say, ‘Wow I have never seen anything like that before’.”

Because the vessels contain overlapping colors, new hues emerge from various viewpoints as secondary colors emerge from primary ones interacting with the planes and bevels in the glass. The science of the eye plays a large role in Hutter’s use of vibrant color, one of the most eye-catching aspects of his work. Amazingly, Hutter is red/green color blind, “ which makes you want to use [bright] colors you can see!” From his days as a glass student at Illinois State, color has played an important role for Hutter as an artist. He remembers how “back in the day at Illinois State they used to unload the annealer of blown vessels and they would have to wear two pairs of sunglasses when they pulled out my pieces because they were wild combinations of colors”. He wears color corrective EnChroma sunglasses at times to see the full spectrum, and describes using color for him as being like a kid in a candy store.

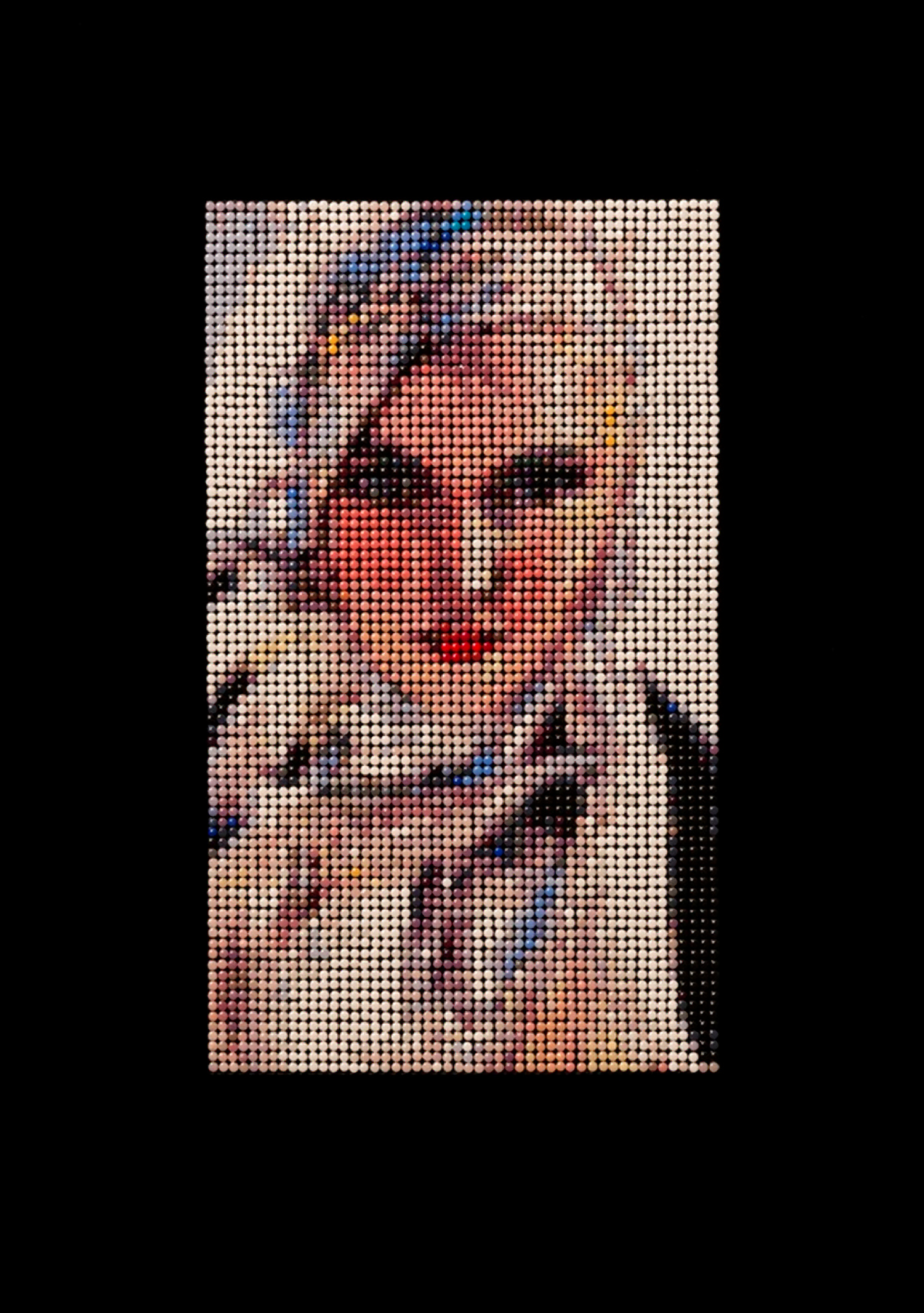

Detail of the White House Vase #6

Among his many accomplishments, Hutter joined the ranks of a rare few American artists and craftsmen when his piece White House Vase #1 was acquired by the White House Craft Collection during the Clinton administration. The piece is now at the Clinton Presidential Library as part of the National Archives, in a collection that acknowledges the important role of glass and other crafts in the echelons of fine art. Hutter explains that there “were many related showings of the collection afterward including one at the National Museum of American Art. It was the first-time crafts were shown in the “big” museum—the Smithsonian.”

Hutter is a fitting choice for the collection, the definition of the innovative American trailblazer. While he never forgets to reflect on the past, he is ultimately a forward-thinking artist and individual. He believes art is a part of how we may heal as a nation from the recent hardships brought on by the pandemic and political upheaval. “When the country rebuilds, I am hopeful a priority will be placed on the arts as a way to move forward” Hutter says. He is always keeping an optimistic eye on the future, both in glass and in life. “I think everyone is going to come out of this with a revitalized hunger for expression, culture, and beauty and all that glass is. We will all have seen the light and that is what I am doing with glass—dealing with the light.” Surely all of us can benefit from following Sidney Hutter into the light.

A short video interview with Sid.

Video created by Charles River Photography

Available works.

___________________